Florence is famous for Renaissance art. But street art plays an important role in the city as well.

The history of Renaissance art in Florence can be intimidating and overwhelming — the city has masterpieces like David and The Birth of Venus.

Even for those who aren’t necessarily big fans of art history, there seems to be this general understanding that the art of the Renaissance has an importance to it.

This can give a feeling of weightiness to Florence as a center of the Renaissance. It can also create the impression that Renaissance art is the standard that art is measured against.

But as you walk to Florence’s world-class museums, you’ll begin to see curious modifications to the street signs, which are done with stickers by a street artist named Clet.

Uninteresting no-entry signs become the backdrop for a spilled wine glass or a watchful cat.

They make navigating through the cobblestone streets of the city less daunting and more fun.

Clet’s signs are everywhere, just as Renaissance sculptures and paintings are. There’s a pleasant surprise when you first see them, then a warm familiarity, and eventually a grateful appreciation.

Isn’t that the same process we have for all great art?

For me, the presence of Clet’s work is important because it helps bring a lightness to Florence. They’re an invitation to engage with the art of the city before you even step into a museum, without pressure.

It is a reminder that art is varied — such a contrast from the Renaissance art held within centuries-old buildings, yet also of value.

You can actually see them, creative street signs and historic paintings, side by side.

Clet isn’t the only example of this in Florence.

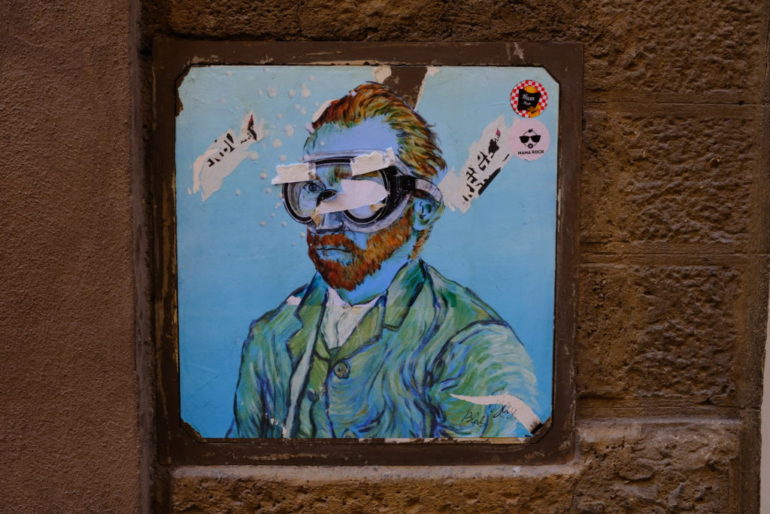

Blub is a street artist who creates portraits of famous people and paintings, but underwater and with scuba masks.

You’ll see them all over — the Mona Lisa, Van Gogh, Girl With a Pearl Earring, each outfitted in the same way.

Blub’s pieces are effective because they take recognizable artists and works of art and use the whimsical underwater theme to make them approachable.

In a museum, you might come across dozens of artists with different styles, influences, and backgrounds. It can sometimes feel difficult to participate meaningfully without a deep understanding of art history.

Blub removes that layer of distance.

One of the things I like most about Blub’s portraits is how they can introduce viewers to new artists, especially Italian ones.

I passed by an image of a woman with bright red hair, blank eyes, and an elongated neck, and didn’t know who it was. After a search, I learned that it was a piece called Portrait of Lunia Czechowska by Amedeo Modigliani, someone I wasn’t familiar with.

When I saw another Blub piece that looked similar, it made sense that it was also by Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne in a Large Hat.

And Blub gets creative in different ways — for example, the type of art covered. Beyond paintings and artists, there are comic book characters.

I hadn’t known about Tex, an old Italian series that was one of the most popular.

Another form of creativity is finding interesting spaces to place the pieces in.

Or adding personal touches to the original work.

Clet and Blub know how they both contribute to the culture of art in Florence. There’s even a Blub piece of Clet, which hangs outside his studio.

But to me, they are more than just additional participants — they are especially important for balancing out the art of the Renaissance.

They, along with other street artists in the city, allow us to better appreciate the richness of the past and present of art in Florence.